today is whatever i want it to be

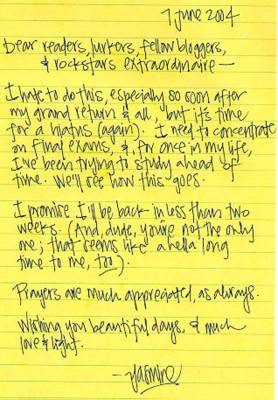

I have so many stories to share with you – insights, conversations, observations, incidents, interactions, meetings – each playing an important role in my two-week hiatus from this weblog.

I don’t even know where to start.

I could tell you about my sister – whose final exams ended two weeks before mine – chauffeuring me sixty miles to school (and back) for nearly a week because most days I was too exhausted to drive. She loves my friends. The feeling is mutual. We’re one big happy family.

I could tell you about sleeping three hours a night, if I did sleep at all, for weeks. And about how pulling all-nighters makes me cold down to the bone, so that even steaming hot showers can’t alleviate the chill for the rest of the day, even in the midst of our blazing Northern California summer.

I could tell you about how I drove home anywhere between 11pm and 2am for two weeks. And about how beautiful the stars look at that time of the night. And about how I barely saw my own family during that time, much less ate a real meal with them.

I could tell you about prayers made in gratitude, and others made for strength and patience.

I could tell you about Somayya preparing for her neurobiology final exam by regaling me with information about the osmotic pressure of urine.

“Why would you even need to know that?” I asked with slight distaste.

“Because,” she answered patiently, “if you’re a doctor and a little kid comes in and says, ‘I can’t pee,’ you have to test him accordingly.”

“Oh.”

“This is why I love pre-med classes,” she said, “because you can actually apply them to real life!”

I could tell you how, an hour later, we (Somayya, my sister, our friend L, and I) met up with a fellow weblogger at an Austrian bakery, and laughed about using the renal system as a pick-up line. Maria is just as beautiful, warm, and approachable as she comes across on her weblog, and she has earned my never-ending gratitude and respect for her immediate attempt to pronounce our names correctly. Interestingly, our conversations touched less on medicine and weblogs than I had expected. Among other things, we discussed reasons why we feel Bush is an incompetent nincompoop. When I confessed that I frequent the bakery just to practice my rusty German (and then proceeded to absolutely butcher the pronunciation of Zwetschgenfleck, or plum cake), Maria solemnly assured me that wanting to know the name of what one is eating is a valid concern. I could tell you that when we all marveled at the fact that she updates her weblog every single day, she replied simply, “You make time for the things you enjoy doing.” Which, I know, doesn’t say much for my writing efforts over the past month or so, but I promise I’ll try to be better. Maria is my hero.

I could tell you about my and my sister’s Islamic Sunday school kids (aged 6-7) presenting in front of everyone and their momma, literally. I’m talking about an entire hall full of people here – parents, grandparents, siblings, and dozens of other people from the local Muslim community. The kids, dressed in their fanciest outfits, were calm and cool, in contrast to our rattled nervousness. I felt like such a mother. I could tell you how, as soon as their presentation ended, two of our kids gleefully folded their fancy-schmancy Islamic school certificates into paper airplanes and launched them into the air. Yes, I laughed.

More than anything, those two weeks were about people and laughter. I remember remarking to someone recently that, after four years, I’ve finally learned to separate the friends from the acquaintances, learned to realize that there is a select group of people I consider close friends whom I know I’ll make an effort to stay in touch with even after college. It amazes me to think that I didn’t even know some of them a year ago. But I am blessed to know the beautiful people that I do, and to be surrounded by them on a near-daily basis.

I could tell you how it has only started to hit me what a transitory state college is. After the recent whirlwind round of commencement ceremonies and graduation parties, I’m left with friends and acquaintances who are still dazed and hesitant about what to do now that college is over. I could tell you about how there’s a Real World out there, about how most graduating seniors I know are terrified of the Real World, and about how glad I am that I’m sticking around for an extra year.

I could tell you about laughing and eating with friends – avocado sandwiches on the rooftop patio, Chinese lunches at the blue tables, pizza dinners in abandoned classrooms, late-night snacks purchased from basement vending machines and sneaked into the library.

I could tell you about taking naps in the library when I should have been studying, about socializing in the library when I should have been studying, about our endless migratory parades from the ground-floor to the third floor to the basement to the reading room and group study rooms on the second floor, shuffling our belongings from table to table, trading batteries and CDs, sharing books and lecture notes, practicing Arabic calligraphy on white boards meant for neurobiology review. And, yet, it seemed as if we did nothing but study. But there was always laughter, even when we were frustrated nearly to tears by stress and studying, even when we had papers and exams in such rapid succession that it left us breathless with exhaustion.

I could tell you about interviewing three students over the course of a week, in preparation for an internship paper on intercultural relations, campus climate, and diversity issues on our university campus. I could tell you about what an amazing experience each of those interviews was, the highlight of my week, about how stimulating and satisfying it is to have in-depth conversations with people who feel as passionately about multicultural issues as I do. E, a White friend of mine, touched me profoundly with her perspective and observations. “In my heart, I would like to be a part of changing the status quo,” she said, “but I think I use ‘I’m busy’ as an excuse not to. I don’t think there are many situations I put myself in where I’m a minority.” I could tell you how true that comment is of me, as well, on a number of levels.

I could tell you about J, another friend, who is actively involved in the leadership or membership of so many groups that he couldn’t even begin to name them all for me. He dislikes labeling himself and thus regularly shifts his identity from Mexican to Native to indigenous to Chicano, and back again. “You can’t ever think you’ve done your best. You always have to do more,” he advised me. “You can never do enough, no matter how hard you push yourself. If you’re thinking you’re doing a really good job, you’re probably not doing enough. Don’t ever be satisfied. You have to be constantly critical and constantly developing into something more, something better.”

I could tell you about how the subject for my third interview was A, the Persian student. It was neither the time nor place to bring up the questions that I had mentioned wanting to ask him. But it was a wonderfully thought-provoking conversation nonetheless, and, like J, he shared so many blunt observations and so much practical advice about campus issues that I’m still mulling over it now.

I could tell you about the recognition ceremony for my internship. Along with fellow interns, I had to speak to a roomful of faculty, staff, professors, PhDs, and University administration-level people about my experiences within the internship over the past year. I know how far I’ve come. I’ve learned how much further I still need to go. But where I am is a beautiful place, too, and I’m so very grateful for the opportunities this internship has afforded me, for the experiences I’ve had and the people I’ve met over the past several months. I’ll be working there another year, and I’d do it for longer if I could.

I have so many stories.

I don’t even know where to start.