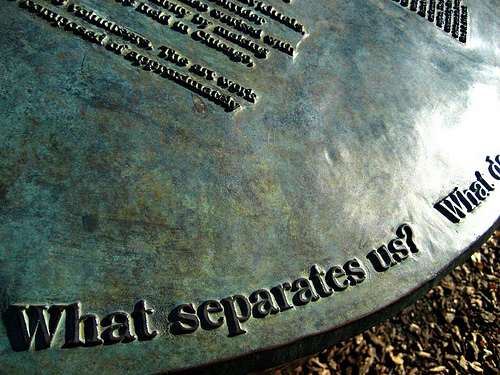

In Chicago: What separates us?, originally uploaded by yaznotjaz.

This is a story about the afternoon I went to Target. And no, it is not about how I walked in to return a few items and buy some placemats and a pack of nails to hammer into the walls for my latest creative project, and somehow, inexplicably, walked out with $130 worth of purchases. Instead, it is a story about what I was wearing.

It was a rainy afternoon, so this is what I was wearing: a dress, a coat, pants rolled above my ankles (I am short, most of my pants are too-long, and I am constantly, accidentally walking into puddles), and — instead of my usual headwrap — a beanie smushed over my hair, with my bangs brushed to the side. Inside Target, as I picked up the items on my mental shopping-list, got sidetracked by yet more items, and zig-zagged my way across the store, I ran into half-a-dozen different Muslim women wearing headscarves. “Wow, there are a lot of hijabis in this city!” I exclaimed inwardly in surprise. Outwardly, I smiled brightly and exclaimed, “Assalamu alaikum [Peace be upon you]!”

And every single woman, without fail, replied very quietly and with a guarded expression, “Wa alaikum assalam [And upon you be peace].”

What surprised me was not the fact that the women didn’t guess on their own that I am Muslim. That’s understandable, given that we often use visual aids as a way of categorizing people, and so a woman like me, who was not wearing an obvious form of hijab, would not have automatically been recognized as Muslim. Rather, what surprised me was: 1. The confusion on each and every single woman’s face when I said, “Assalamu alaikum” (Why? Do they think only hijabis are “Muslim enough” to say salaam?), and 2. The lack of smiles in response to mine (Am I scary? Do they consider it a personal affront that I wasn’t wearing “proper” hijab that day yet deigned to say salaam? Are people in my city simply unhappy people who hate smiling?).

I gave the first few women the benefit of the doubt: Maybe they were disgruntled about the cold and rainy weather, perhaps they were sick, maybe they were preoccupied with their children, perhaps they’d had a terrible day. Maybe no one wants to see a happy, smiling girl on a crappy day when you want to stab everyone; it just makes you crankier. I tried not to overthink the whole thing too much — I didn’t want to feel defensive, blow things out of proportion, or over-analyze something that was possibly just a trivial, mundane interaction. But by the end of my Target shopping experience, when I’d run into no less than seven different hijab-wearing Muslimahs in various parts of the store, ranging from the makeup aisle to the office supplies to the home decor to the checkout line, I found myself rattled by the lack of smiles in response to my cheery, “Assalamu alaikum!”

Months ago, a Muslim woman I know posted the following facebook status, a beautiful little story that I’ve remembered all this time:

“An elderly lady kept smiling at me at Trader Joe’s. Every time we made eye contact, she grinned from ear to ear. Now I understand why the Prophet Muhammad [peace be upon him] said, ‘Even a smile is charity.’ I feel like someone just gave me a million bucks for free.”

Smiles are a classy and dignified form of acknowledgment. There is a simple power inherent in them. A smile doesn’t have to mean, “I recognize that we are the same.” It could simply mean, “I acknowledge that we share this world, and I notice that we have crossed paths today for this millisecond, even thought we don’t know each other and may never see each other again.”

Each time I briefly interacted with yet another headscarf-wearing Muslimah who didn’t smile back at me, I walked away extra-conscious of my pants rolled above my ankles, my bangs brushing out from under my hat. They should see me on other days, when I wear sweaters with elbow-length sleeves or roll up my pants to my knees at the beach. Sometimes, when taking the garbage out to the chute at the end of the hallway of my apartment building, I even walk down the hall with my hair completely uncovered. The Target interactions made me feel defensive, even when there was no need to feel so.

In a sociopolitical climate in which many Muslims are wary of possible stereotyping and ignorance and hate from those who are Not Like Us, I have surprisingly found that the least understanding actually comes from my own family and other Muslims: “Why do you wear your scarf that way?” pointedly and repeatedly ask my aunts, and my cousins’ wives, and now even my tiny nieces & nephews. “Why is your neck showing!?” ask others.

“To annoy you,” I’ve come to retort. (It sounds even ruder in Hindko, which affords me brief moments of spiteful satisfaction.)

I tried to pep-talk myself out of hurt and exasperation. Perhaps all the unhappy Muslimahs in my city had chosen to visit Target that day; there must be other, nicer ones around somewhere. Or maybe I was just taking all this too personally, anyway. The lack of smiles didn’t equate to judgment; it just mean they were confused about how to categorize me. We’re human, we categorize people; it’s what we do.

On my way out of Target, I stopped briefly at the indoor coffeeshop to order a hot chocolate. Standing in line in front of me were two children, a boy and girl aged 5-7, along with their father. The little boy wore a bright-blue hearing aid in each ear. I surreptitiously glanced at him a few times as the line moved progressively forward; finally, as the little boy turned towards me, I smiled at him and said, “I like your hearing aids!”

“Thank you,” he mumbled shyly.

“Mine are red!” I said, and lifted my beanie above one of my ears. He smiled a tiny smile and nodded, his sister glanced at me curiously, and the father, in the midst of ordering their drinks, turned and smiled widely at me. That gesture of sharing my own hearing aids would have been nearly impossible on any other day, with my tightly-pinned headwrap usually covering my ears.

And so, on an evening in which the lack of smiles from my fellow Muslimahs felt like a stinging rebuke, I found that my spontaneous act of sharing something I rarely discuss in public, the acknowledgment of that personal condition and experience, and the family’s smile in return acted as a balm, soothing the bruise of non-acknowledgment from those whom I’d expected to feel most relatable to.

Who cares about headscarves and cranky Muslims? If I can get a smile out of a little boy over the fact that our collective ears all run on Duracell batteries, that’s good enough for me.

Once home, mulling all this over in my head, I realized this was not a story about what I was wearing (then again, perhaps it was, but I choose not to classify it as such). Rather, this was a story about open-heartedness. I remembered something I always try to live by: Other people have a choice in what they wear at home and when they go out into the world — their solemnity, their joy, their judgment, their truth, their sneers, their laughter, their lack of smiles. I can’t force people to smile, if they don’t at all feel inclined to do so (and, let’s face it, I have little patience for coaxing them).

But I, too, have a choice — to bring my heart in full force, wherever I may go.

Even if it’s just to Target, for a pack of nails.

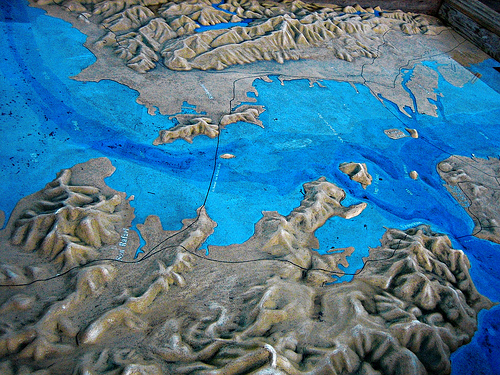

In Chicago: What connects us?, originally uploaded by yaznotjaz.